“A Who’s Who of pesticides is therefore of concern to us all. If we are going to live so intimately with these chemicals eating and drinking them, taking them into the very marrow of our bones – we had better know something about their nature and their power.”

― Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

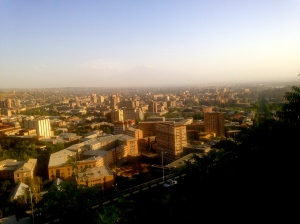

In my admittedly limited experience (about 3 weeks), I have not found air pollution in Yerevan (or elsewhere in Armenia) to be a problem. I know there is the usual amount of urban air pollution from automobile exhaust, and sometimes I can smell it, but for the most part, it seems to me no worse (and far better) than most other cities I have visited.

One can see smog that settles into the Ararat Valley in the afternoon and the evening, and it obscures the view of Mt. Ararat, which is just 60 km away. (Ironically, and sadly, the car trip is nearly 700 km and takes around 13 hours – not accounting for traffic or road conditions – because Mt. Ararat is in Turkey, and with the border to Turkey closed, one must go there via Georgia.)

The water supply is fresh and delicious – in fact, Yerevan is the largest city in the world that is fed entirely by springs. There are spring-fed water fountains throughout the city with cold, tasty water.

But, despite clear skies and clean water, there are toxins and particulates to worry about.

Professors Artashes and Natalie Tadevosyan have spent their careers studying environmental and occupational pollutants and their effect on health. They recently published data from their ongoing study of pesticide residue in breastmilk which showed that between 70% and 100% of breastmilk in their study was contaminated with organochlorine pesticide residue, including DDT, which has been outlawed here and in much of the world since the early 1970s (Tadevosyan and Tadevosyan, 2012).

The problem is that some people stockpiled DDT after the Soviets made it illegal in the 1970s; moreover, they can buy it from China and other places on the black market. Farmers use pesticides on their crops and use it to protect livestock from flies, mosquitos, and other insects, and there is evidence that urban people use harsh pesticides in their homes to prevent insect infestations. Even worse, is the fact that DDT can remain in ground water, soil, and the human body for years, and break down into DDE. Most people on the planet have detectable levels of DDE in their bodies (see University of California, Berkeley, Center for Children and Environmental Health), but DDT/DDE in breastmilk suggests that the contamination was more recent and the body has had less time to start to metabolize it into the organ systems.

In addition to the very important findings about breastmilk content (and thus prevalence of pesticide use and contamination in the human population), the Tadevosyans found that prevalence in two regions was strongly and significantly associated with poor perinatal health outcomes, including complications in pregnancy, miscarriage, and preterm delivery. They conclude that environmental protection policies must be invoked and enforced and that agricultural pesticide use should only proceed using legal chemicals and following correct protocols (e.g., wearing masks and other protective clothing). Careful washing fruit and vegetables prior to consumption can remove the majority of pesticides, but residue remain in meats, fish, and soil.

What else can be done? The Tadevosyan’s study is ongoing and their longitudinal data on breastmilk content and obstetric history remains critical.

Simply telling farm workers and rural residents to stop using pesticides would not work. Moreover, when people count on good crop yields for their livelihood (like the woman in the photo above), they have a significant investment in making certain that insects do not ruin crops.

What about telling women not to breastfeed? Encouraging the use of infant formulas to avoid transferring the pesticides from breastmilk to infants? While this does not represent normally accepted public health practice, the benefits in infant growth and neural development could be substantial.

Answers are never easy.

References

Tadevosyan, N., & Tadevosyan, A. (2012). Dynamics of organochloride compounds identification in rural female population of Armenia and related health issues. The New Journal of Armenian Medicine, 6(3), 67–74.