From a lecture presented at the International Conference on Non-Communicable Diseases, Cluj School of Public Health, NIH/Fogarty Institute, May 2015.

Let me tell you a story.

In 2013 I was asked to co-lead a research-based study abroad trip to rural South India to evaluate a community-based diabetes treatment program.

Diabetes is not my bag.

I was trained in maternal and child health (MCH) and I focus on global aspects of reproductive epidemiology. My work in India has centered mainly around maternal and child health. I have visited many rural villages and urban slums with no sewage and little or no fresh water, I have visited leper colonies, I have seen the havoc of diarrheal disease in children, and I have studied behaviors related to mosquito-borne disease prevention. The Indian infant mortality rate remains very high (about 40 per 1000 live births in 2013), maternal deaths are common (about 200 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2013) (World Bank data), and signs and symptoms of malnutrition are everywhere.

So, diabetes?

As my mind glossed through my past trips to India, I recalled a cricket match in Delhi. The Feroz Shah Kotla cricket ground was filled to capacity for an IPL (Indian Premier League) match against Pune. It struck me that virtually everyone, children, adults, everyone, was overweight. Everyone. While there are cheap seats in a cricket stadium, it requires some cash to attend. The vast majority of these cricket-goers were comfortably middle class.

Hence: diabetes.

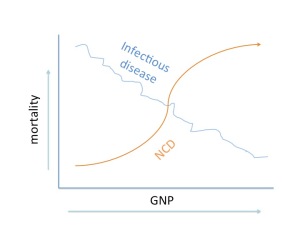

The epidemiologic transition is a model showing how disease and cause of death change with demographics and economic growth. The first image below shows the classic relationship between economic development (illustrated by GDP) and causes of death. Mortality in countries with the lowest GDPs arise chiefly from infectious diseases such as malaria, diarrhea, and viral infections. With greater economic development, the main causes of mortality shift from infectious disease to non-communicable diseases, such as heart disease and diabetes.

In the US and Europe, relatively few deaths are caused by infectious disease; average life spans surpass 75 years and people eventually die of cancer or heart conditions. A problem unique to prosperous nations are increased prevalence of lifestyle-related NCDs, such as diabetes. In the US, diabetes is practically epidemic: 9.3% of Americans have type 2 diabetes (29 million people). We know Americans are overweight – fully one-third are obese – and most do not get enough physical exercise. Diabetes often requires long-term treatment and brings with it co-morbidities and high financial costs – to wit, the CDC reports that the estimated annual medical cost of obesity in the US was $147 billion in 2008 dollars; moreover, the medical costs for people who are obese were $1,429 higher than for those of normal weight (http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html).

Europe, particularly some countries and sub-regions, is not terribly far behind the US in high prevalence of lifestyle-related NCDs, with a regional prevalence of 8.5% (International Diabetes Federation, 2014). Prevalence of diabetes in Europe ranges from 2.1% in Iceland, 5% in the UK and lower in Scandanavia to about 12% in Germany; rates in the newly admitted EU countries of eastern Europe are rising quickly.

Here’s a twist on the standard thinking about diabetes and other lifestyle-related NCDs: we generally think that higher GNP equals higher rates of NCDs. That’s generically true. But, think about associations based on individual (or group-level) socioeconomic position (SEP), where higher SEP is associated with less likelihood of obesity, better access to healthcare, and less sedentary behavior. This observation makes our curve look more like:

But a funny thing happened on the way to the forum: rising middle class people in lower-income countries are more likely to be at risk for lifestyle-related NCDs than their middle class counterparts in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand.

One explanation is that some regions and cultures retain the notion that one shows rising economic status with not only less physical activity and more intake of processed foods, but with a status symbol waistline. In many places, a fat family is a prosperous family, and the curve would look more like:

So let’s turn back to India, where we see precisely this phenomenon. What is surprising – at least to the western eye – is that the epidemiologic transition is happening at the village level (as well as the regional, state, and national levels). In a single village or group of villages, scheduled caste (so-called untouchables) and tribal people are still dying of malnutrition, childbirth, and diarrheal disease, while their near-neighbors of higher caste are eating increasing amounts of white rice, sugar, and refined carbohydrates. The idea that Indians are genetically predisposed to abdominal adiposity and diabetes is reasonably well-established. The fact that their girth, eating habits, and lack of exercise suggests status confuses our usual preconceptions about SEP and health.

This dynamic also suggests that we need a more complex theoretical model for examining the epidemiologic transition – one that recognizes differences in local culture and social position and further suggests better preventive tactics.

What is to be done?

A first step is to rethink how we model global health, including development and resulting demographic and epidemiologic change. A better model would consider variables at the global, national, regional, and community levels, including indicators of SEP, access to healthcare, and cultural attitudes about behaviors associated with NCDs. This model would acknowledge resources and risk factors at each level, characterizing each as measurable variables that can be weighted and entered into a multilevel regression model, assessing how each level affects the whole while controlling for other inter- and intra-level effects.

For example, we might surmise that at the global level, risk variables could include availability and distribution of food and medicines, costs of pharmaceuticals, global media influences on diet (advertising) and desirable behaviors, and commercial and trade boundaries that would limit/expand particular crops, such as tobacco. At the national or state level (depending on country infrastructure), political will and resources may be critical for not only enacting legislation (e.g., food programs) but enforcing new policies (e.g., actually distributing food). Collective demand for universal healthcare is also important; demand must precede political will and implementation. In some former Soviet countries, such as Armenia, there is no national healthcare payment system, so while patients may use government hospitals, they pay practitioners for services, sometimes in money and sometimes in kind. In India, access to healthcare varies by state, as do policies related to availability of antenatal care. At all levels, corruption can sabotage the entire system.

Second, assuming we develop a more complex model for understanding the dynamics of disease prevalence, we have to gather better data from all countries on NCD prevalence, including injuries. Most NCDs – certainly diabetes – are underreported. Data are even less reliable in lower income countries and real prevalence is probably more variable across regions. For instance, data sources for diabetes are based mainly on surveys and some clinical and hospital admissions or release data. Cancer surveillance is strong in developed countries, but represents a considerable logistical challenge in less developed countries, including the new entrants to the EU. Overall, better data will lead to more effective (and evaluable) prevention and treatment strategies and provide benchmarks for understanding change in populations over time.

My recommendations? Proceed to understand variables at multiple levels and identify measurable factors to target for improvement across local and national health and social systems. At the global level, funders must move away from small NGO-driven interventions that are neither evaluated nor scalable, toward policies and programs that improve infrastructure at all levels, include the development of strong data collection and management systems, and support evidence-based change.

[Text based on plenary presentation given at the First International Conference on Non-Communicable Disease, Cluj School of Public Health, Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, May 2015.]